Methodological Mutualism: Rethinking the Agency of Local Communities in the Belt and Road Initiative

By treating the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as an agentive power, many analyses fail to see the agency of those framed as affected by the BRI (cf. Alff 2016). In this blog post, I aim to address this issue by exploring how we can ascribe agency to the local communities intertwined with the BRI. With a focus on women's economic agency in the Sino-Kazakh border regions and infrastructure embodied in the BRI, I propose a paradigm shift towards methodological mutualism, which allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between the BRI and people on the ground.

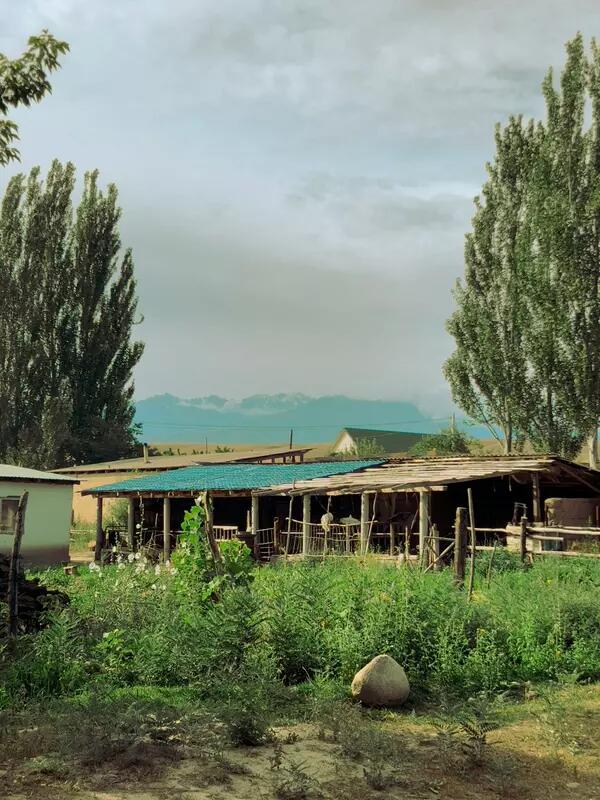

Methodological mutualism—a concept inspired by the notion of symbiotic anthropologies—recognizes the mutual symbioses between people on the ground and the BRI, considering their interdependencies and the nuanced nature of their relationships. While this mutualism can be positive and empowering, it can also involve nuisances and disadvantages for the stakeholders involved. For example, roadside restaurant owners in the Sino-Kazakh border town Zharkent experienced a decline in customers when the construction of the "Western-Europe Western-China" highway bypassed the town.

By embracing a methodological mutualism, we can move beyond the traditional discourse surrounding how the BRI affects other countries by integrating the bottom-up effects of the BRI into our analyses. This shift in perspective acknowledges the agency of the people commonly considered as being affected by the BRI and complementary raises the question of what these individuals do for the BRI.

The BRI in Kazakhstan and local perspectives

The BRI's impact on the Sino-Kazakh border manifests in various forms, both physical and regulatory. While the term "BRI" remains unfamiliar to local traders of Zharkent, the concept of the "New Silk Road" resonates deeply with them, evoking a sense of pride and historical identification. However, it is crucial to emphasize that these traders, the majority of them Muslim ethnic Uyghurs, perceive the BRI through the lens of distinct infrastructure projects rather than as a revival of the Silk Road. For example, the Kazakhstani state infrastructure program, Nurly Zholto which the BRI label was added (Joniak-Lüthi et al. 2022: 2), resonates more strongly with the locals than the BRI.

The large BRI hub in southeastern Kazakhstan is commonly referred to as Khorgos by both international media and people on the ground. Khorgos is an agglomeration of several infrastructure projects and institutions, including: a dry port where shipping containers traveling between East Asia and Western Europe are transferred to another railway gauge; a largely deserted train station called Altynköl where passenger trains commuting between China and Kazakhstan stop; and a newly constructed town, Nurkent, which hosts labour migrants, such as engineers and other experts, who work in the planning, construction and operation of the various Khorgos facilities.

Most impressively, in 2018 one of Central Asia´s largest border crossings under the name Nur Zholy began to operate in Khorgos. In Khorgos, what began as informal cross-border trade after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, turned with the BRI into the special economic zone International Centre for Cross-Border Cooperation (ICBC), which the Chinese and the Kazakhstani governments administer equally. The ICBC consists of several large shopping centres that sell textiles, household goods, food items, and fur, among other products. Visitors can enter the ICBC without a visa. Its main purpose is to attract investors who eventually help it grow into a city (La Mela 2022). During the time of research between 2016 and 2019, there were mostly Chinese and Kazakhstani tourists present and, most remarkably, shuttle traders.

Shuttle trade

Informal cross-border trade in the form of shuttle trade is a phenomenon widely reported in ex-Soviet border regions (Mukhina 2014), where it emerged due to a shortage economy in the former Soviet Union. While shuttle trade ceased in most places with the collapse of the Soviet Union, it continues to thrive in Khorgos. One reason for this, I suggest, is the mutual interdependence of local shuttle traders with the functioning of global supply chains operating via Khorgos. As observed during my 16 months of ethnographic field research in the Sino-Kazakh border region and as confirmed by locals, the majority of shuttle traders is female.

One remarkable individual is Gulnara, a widowed Uyghur woman in her late 50s who nowadays runs her own canteen. This would not have been possible without the cash she earned as a shuttle trader in the 1990s:

I used to chop wood and stoke the fire. Then I started going there [the border] everyday, working with different companies […] that’s how I survived in this life.

As shuttle traders, women carry a limited amount of goods daily across the border. This is physically exhausting work: taking into account queues at the customs control and waiting time for taxis and shuttle buses, a working day may easily extend to 16 hours. The exhaustion eventually led Gulnara to abandon her shuttle trade occupation until cross-border trade began to formalize in the late 2000s. At that time, my interlocutors stated, more and more logistics companies entered the market and regularly hired shuttle traders to coordinate their operations. Gulnara was invited by one of the logistics companies to work for them as a coordinator of shuttle traders:

The company used to give me 300,000-500,000 Tenge ($2,000-$3,400 USD) in the morning. Every in-charge had 15-20 people in a group. I paid them their salary. The money has nothing to do with the goods. It’s the company’s business. The company was just transporting goods this way. Let’s say, they have 50 tons of goods, so how to cross it through the border? They were sending a group of people, with registered documents to transport the goods.

As reported by other locals, logistics companies hiring shuttle traders on a regular basis was an established informal procedure, which served to maintain the flow of goods across the border. Border crossings tend to turn into bottlenecks (cf. Carse et al. 2020) where goods are stuck due to time-consuming customs procedures. Shuttle traders fix those gaps.

Many women have similar stories to tell as Gulnara, which is why I propose to frame shuttle trade as a window of opportunity. These limited periods enable individuals, and particularly women to capitalize on the possibilities presented to them, highlighting their agency in engaging with the BRI. Specifically, I focus on women who have successfully harnessed economic opportunities through shuttle tradeand petty trade.

Cash invested in “playing chai”

Another intriguing facet of these women's economic activities is their practice of investing the cash earned through shuttle trade into a local social activity known as "chai," which directly translates to "tea" and is exclusively reserved for women. Chai is more than just a social gathering; it is a cornerstone of community life. Women participating in chai typically convene weekly or biweekly, with groups consisting of 6 to 10 individuals, taking turns to host the event. Chai operates as a rotating loans scheme, resulting in women being permanently indebted to one another. This financial mechanism fosters trust and cultivates strong bonds among the participants, who generally reside in the same town or village. Chai is prevalent in the border town of Zharkent, with an estimated 80 percent of women actively participating on a regular basis. Rahiläm, a woman in her 60s who partakes in chai, enthusiastically expresses:

Close relatives can live at a remote distance and are rarely seen, but in chai each one is a sister or a little sister for us, therefore we have such a friendly, close-knit, kind and good aura within our company [chai group].

Yet, it is not just about finances. The social dimension of chai holds immense importance for these women. During chai gatherings, they come together for lunch or dinner, indulging in food and beverages, dancing, laughing, and sharing stories and news. These moments go beyond the economic transaction; they form the social fabric that sustains their lives. This interconnectedness is especially crucial in a context where women feel neglected by both men and the Kazakhstani state. Djamila, a Uyghur woman in her 40s, expresses her sorrow:

Most of the men are unemployed now. And almost all the women work. There’s no proper job for men here now. All the jobs are taken by women. I guess men have quite a low self-esteem now, they don’t respect themselves much because they are unemployed. That is the reason why they are nervous and aggressive. We are Uyghurs and as every Turkic ethnicity, we treat men as number 1. And nowadays, when the man doesn’t work, the woman can debase him. It’s not right. We don’t listen to them, we tread on them. Islam says that a man is the second God. A woman has to obey, this makes a full nuclear family. But he has to earn enough for that. Only then a woman will obey.

In her quote, Djamila points to various ongoing shifts in values. Most ethnic Uyghurs have described themselves as becoming more religious since the opening of the Sino-Kazakh border in 1987 (Grant 2020: 2) and the subsequent increase in cross-border interactions. They hold Muslim values and gender ideologies in high regard. Simultaneously, they appreciate "Westernization" values related to working women and career development.

Given women´s perception of Uyghur men as unreliable and their awareness of disadvantages faced as a minority ethnic group in Kazakhstan, chai serves as a social safety net. The female bonds formed during these gatherings extend beyond the meetings themselves, infiltrating everyday social and ritual life. For instance, women adhere to an informal agreement to support each other when needed. This support encompasses the organization, preparation, and execution of ritual feasts, which are traditionally elaborate in Central Asia and involve hundreds of participants and whose organization often rests on the shoulders of women. Additionally, these chai networks extend to the provision of emotional support, as explained by Rahiläm:

They [chai members] all support me in difficult times; we can all rely on each other. This year three of the people closest to me passed away, so those [chai] friends were there for me, they joined me when I had to go to the graveyard, they supported me emotionally.

In essence, chai is more than just a tea-drinking gathering; it is a symbol of resilience, mutual support, and empowerment. It highlights the strength and resourcefulness of Uyghur women who, in the face of challenges, have found a way to uplift and sustain each other, creating a vital safety net in their community. The mutually beneficial connection with the BRI plays a crucial role in the women's path to empowerment.

Conclusion

Shuttle trade and other economic activities enabled by the BRI emerge as pathways to economic empowerment for women. By facilitating the movement of goods across borders, women generate income and invest in social relationships, demonstrating the multifaceted nature of their economic endeavours. Notably, the relationship between the BRI and women engaged in shuttle trade is characterized by mutual interdependence. Women play a crucial role in the BRI's logistical operations, bridging gaps and ensuring the uninterrupted flow of goods during disruptions and crises.

To overcome the methodological hierarchy and victimization of those affected by the BRI, it is essential to embrace a methodological mutualism that acknowledges multiple agencies at play. By examining the symbiotic relationships between the BRI and local communities, it is possible to develop a comprehensive understanding of their intertwined dynamics. This approach fosters a more inclusive and nuanced analysis of the BRI, promoting agency and mutual understanding of the stakeholders involved.

Bibliography

Alff, Henryk. 2016. ‘Getting Stuck within Flows: Limited Interaction and Peripheralization at the Kazakhstan–China Border’. Central Asian Survey 35 (3): 369–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2016.1210860.

Carse, Ashley, Townsend Middleton, Jason Cons, Jatin Dua, Gabriela Valdivia, and Elizabeth Cullen Dunn. 2020. ‘Chokepoints: Anthropologies of the Constricted Contemporary’. Ethnos, May, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2019.1696862.

Grant, Andrew. 2020. ‘Crossing Khorgos: Soft Power, Security, and Suspect Loyalties at the Sino-Kazakh Boundary’. Political Geography 76 (January): 102070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102070.

Joniak-Lüthi, Agnieszka, Alessandro Rippa, Jessica Clendenning, Jessica DiCarlo, Matthew S. Erie, Max Hirsh, Hasan H. Karrar, et al. 2022. ‘Demystifying the Belt and Road Initiative’. Fribourg, Munich and Boulder. https://bri.roadworkasia.com/.

La Mela, Verena. 2022. ‘Khorgos – the Making of an Unequal Twin on the Sino-Kazakh Border’. In Twin Cities: Borders, Urban Communities and Relationships over Time, by Ekaterina Mikhailova and John Garrard. Second Volume. London and New York: Routledge.

Mukhina, Irina. 2014. Women and the Birth of Russian Capitalism: A History of the Shuttle Trade. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501758157.