Bringing a Politics of Sight to the BRI: In/visibility, Infrastructure, and Global China

As the Transformations blog series demonstrates, scholars continue to call for grounded and localized research on China’s global engagements (Bentley, 2022; Karrar, 2022; La Mela, 2024; Oakes, 2021). Yet, there are many conceptual and empirical ways to approach such research. Here, I suggest an approach centered on in/visibility and a politics of sight, based on several observations related to the visibility of projects themselves, the diverse views that people hold on the BRI, and how the effects of projects are either illuminated or concealed.

The BRI’s hypervisibility is undeniable. Ambitious endeavors, from regional train systems to new cities and colossal dams, are markers of the initiative. Public and policy attention tends to fixate on the scale of projects or speculate about the intentions driving Chinese involvement, thereby overshadowing the less visible practices and effects that underpin and sustain its production (e.g., related to labor or local marginalization). Additionally, views on the BRI are often homogenized. I am frequently asked: “What do people in X-country (e.g., Laos) think about the BRI?” This framing tends to portray countries and their populations as homogenous in their perspectives or experiences. At the same time, the BRI has gained a reputation as elusive, opaque, or challenging to define. Some scholars suggest vagueness is intentional, positioning the BRI as an invitation, “a notion, a gesture, the beginning of a sentence waiting to be completed by someone else” (Oakes, 2021). From this perspective, ambiguity enables the BRI to adapt to diverse contexts and maintain flexibility for state and capital interests.

Both hypervisibility and invisibility operate as desired outcomes that render the BRI legible. It is imperative to attend to the tensions between hypervisibility and invisibility, and specifically the diverse and less visible experiences, uneven effects, differentiated views, and complex relations behind hyper-visible projects. The challenge thus extends beyond the visibility of projects themselves to understanding the implications of what is made visible and what is concealed. In essence, the BRI’s political, cultural, and social effects are contingent on what is brought to light and what is kept in the shadows (see, for example, DiCarlo 2024). How, then, do people see the BRI? For whom is the BRI hyper-visible or invisible, and what might either obscure? What do these perspectives reveal about the BRI and China’s global integration? I suggest adopting a “politics of sight” to navigate the tensions of opacity and spectacle, understand the performative nature of development, challenge prevailing narratives, and grapple with seeing or not seeing the BRI means.

Infrastructure between opacity and spectacle

Over the past decade, researchers have examined infrastructure development through various frameworks, with the infrastructural turn producing compelling analytical lenses through concepts of visibility and invisibility (Star, 1999; Larkin, 2013; 2020). Infrastructure’s visibility, however, varies – at times emerging during breakdown (Schwenkel, 2015), and at others, it is inherently woven into daily life. In some instances, visibility is intentional, acting as a spectacle that might elicit awe or fear (e.g., Larkin 2020). Conversely, as projects multiply and integrate into their surroundings, ubiquity diminishes their visibility.

Infrastructure, then, is more productively understood on a spectrum of visibility, ranging from opacity to spectacle (e.g., of projects) on the one hand and as both revealing and concealing (e.g., processes and effects) on the other. This spectrum raises important questions about the perceptions and effects of infrastructure. Pachirat’s (2011) “politics of sight” proves useful in addressing these questions. Drawing on Pachirat, scholars have shown how violence in contexts like slums and slum tourism is outsourced or concealed to make it less visible (Davis, 2006; Henry, 2020). Similarly, infrastructure development masks violence under the guise of progress, often accepted as inherent to capitalist development. Applying a politics of sight to infrastructure exposes tensions between spectacular development and the everyday experiences shaping places and lives (such as dispossession, unequal labor practices, and performative development), providing insights into what constitutes the BRI and how people understand it.

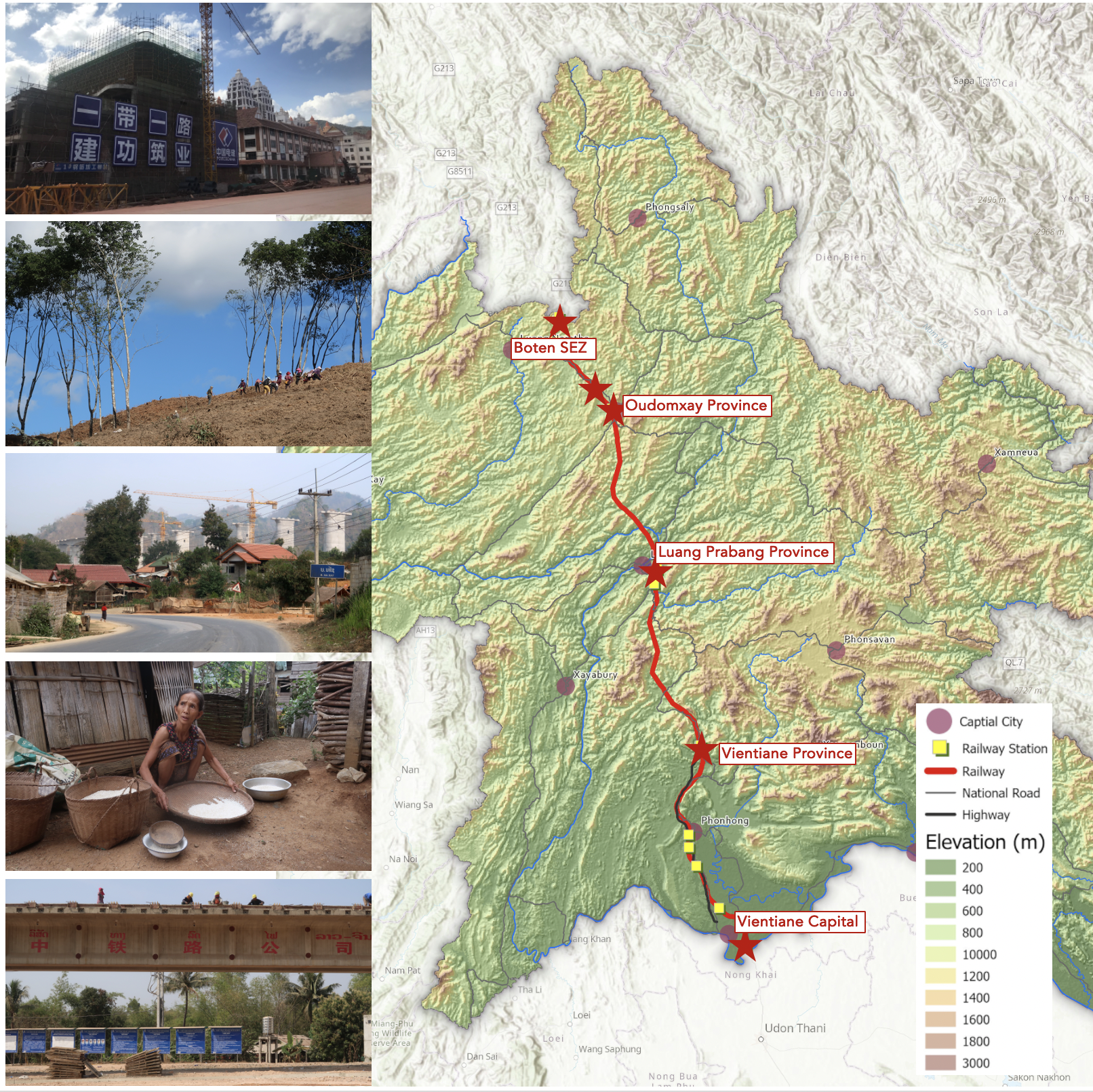

Views from the Laos-China Corridor

In what follows, I draw on interviews from across the Laos-China Corridor to detail the varied development experiences and imaginaries related to several BRI projects in northern Laos.

1. On the “Chineseness” of projects

Despite the prevailing notion of Chinese dominance through infrastructure, local perceptions often diverge. Projects are not necessarily framed through their “Chineseness” but within a larger constellation of development efforts involving the host state. Conversations with local people along the Laos-China Railway (LCR) underscored how they tend to view the project as an initiative of the Lao state, highlighting the influence of local politics on their ability to participate in or challenge the project. Here, a politics of sight challenges the common “China threat” narrative associated with the global boom of large Chinese infrastructures, instead shedding light on challenges related to the Lao government, local politics, and a lack of trust in officials and local political processes. It also shows how people focus on a project’s immediate effects and how they are treated throughout development.

Despite the significant media attention on the railway’s rapid progress, referred to as China speed, local perspectives between 2017 and 2023 did not necessarily align with narratives on Chinese-backed projects in international and regional media. Rather than encountering the “BRI” or “China,” they understood projects through encounters with local officials and policies. For most villagers, local officials serve as the main point of project contact, with limited interaction with construction companies and Chinese workers. Several people also reminded me that Chinese construction companies must seek direct approval from the central Lao government to proceed swiftly with construction. The Lao government facilitated the removal of people, homes, and agricultural land for the railway, such that the most visible bureaucracy was the host country. Some people who lost their land even speculated that Chinese workers or companies might have handled the situation better. In some cases, they noted that Chinese workers supported local businesses or allowed them to complete agricultural cycles.

2. Development theatre, performative labor, and the BRI banner

The BRI’s in/visibility extends beyond physical infrastructure in another way: to the labor of workers tasked with creating a façade of development. Their daily lives become a stage for enacting the initiative, a performance akin to development theatre that renders the BRI visible and “successful.” However, this vibrant façade often masks the everyday challenges workers face.

The experiences of laborers constructing a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) at the border illustrate these points. Their lives oscillate between monotonous tasks and the production of small-scale events designed to create an illusion of luxury for visiting elites. Despite the exhausting nature of their work, laborers played a pivotal role in crafting the SEZ’s visibility during high-profile conferences and events. This performative labor, akin to development theater, renders the BRI visible to some. However, the vibrant, thriving city dissipates as guests depart, leaving a stark contrast between the heightened activity and vacancy.

Many workers live in this rhythm of hype and lulls as they produce and sustain the vision of the SEZ, which in turn shapes how they see the BRI. Seen in this context, the BRI relies on the imaginative labor of workers who embody and enact the zone’s development. This positions people in relation to the BRI as performers and audience, producers and consumers. In this way, workers play a crucial role in crafting the visibility of the BRI, which overshadows their challenges related to low pay, unrelenting work, boredom, and more.

The performative labor of workers from below is matched by the legitimacy engendered by the “BRI banner” and Beijing from above. The BRI banner and performance of an SEZ-in-the-making signaled to developers and investors that projects were too significant to fail. Various groups, including migrant workers, investors, and small business owners, were willing to invest their time, labor, and capital in the zone. Chinese individuals and companies increasingly viewed the zone as a “good investment” due to the workers’ performance of zone futures and the BRI’s façade of state-backing.

3. (Not) seeing the BRI

Not far from the SEZ, however, a Lao woman asked as we started an interview, “What is the BRI?” I had not expected such a

question, especially since we sat only a few kilometers from new railway tracks. We offered standard definitions and examples of the BRI. Another woman interjected to explain that Chinese people and projects are nothing new for them, and these projects were like many others. Chinese pop music played on the radio in the background as if to drive the point home. This conversation highlighted tensions in how people see or do not see the BRI amid a broader history of development and regional relations. For them, BRI projects are a continuation of development and investment trends. In turn, they did not see themselves in relation to the BRI.

This point was reinforced in 2023 when I returned to a village near a railway station and asked what people thought about BRI now that the railway was operational. According to one person, his village knew nothing about the BRI: “We have no idea what that means. And it does not matter what we think about it.” I pressed him on the last point. He agreed his community frequently discussed projects and their benefits but not “the BRI.” He reminded me, “People outside the capital do not talk about the BRI.” Instead, they focus on what they see day-to-day: construction, labor, and what they might gain. A Lao friend suggested that those near main roads might have started to notice and attach meaning to the BRI. However, “people living far away do not know how [the BRI] works … [it] is too far away for villagers and local officials.”

4. Varied views from the capital

The BRI comes into sharper focus in Vientiane, where diverse perspectives emerge. For example, state officials, including ministry and National Assembly representatives, often sought legitimacy through large projects. Conversely, bureaucrats and technocrats, especially in the energy sector, emphasized financial benefits and overall energy system efficiency, regardless of an infrastructure’s national origins. A planning expert noted how the sheer scale of infrastructure projects can sway officials who were initially hesitant about their impact: “The gigantic, concrete structure is like nothing most Lao people have ever seen…everything about the structure and its purpose points to the future.” In many ways, officials saw themselves in relation to the success or failure of the projects they pursued.

Beyond officials’ views of BRI projects, some Vientiane residents also spoke favorably of the BRI, highlighting economic opportunities, job creation, improved transportation, and increased tourism. However, concerns lingered about project sustainability. One resident explained, “We do not know how long the transportation benefits will last for people taking the train.” There were also concerns about the time it would take for the promised poverty alleviation benefits to materialize. Still, many expressed a sense of optimism. Like workers in the SEZ, hope was anchored in the notion of future possibilities. While optimism prevails for some, others in the capital who lost land for construction are less hopeful. The most skeptical characterized the BRI as a way for Laos to become an “external province” of China.

Conversely, individuals tied to small companies or Chinese business organizations in Vientiane viewed the BRI as a lucrative opportunity. For them, the initiative is more than large-scale infrastructure, encompassing sectors like trade, manufacturing, logistics, finance, and tourism. These businesses, recognized by the Chinese government as crucial BRI contributors, receive financial incentives, policy backing, and diplomatic assistance. For these entities, the BRI extends beyond infrastructure, making them both beneficiaries and ambassadors of the initiative.

5. Proximity and temporality

Reflecting on the preceding experiences, it is clear that a politics of sight entails spatial and temporal components. Proximity influenced conceptualizations of the BRI, shaping views based on exposure to projects, news, investments, and labor. In the capital, there was heightened geopolitical awareness, while border regions experienced the BRI differently, seen as either an economic catalyst or an impediment to traditional trade routes. Even more distant perspectives, such as those from US or European offices, often overlook the social and material dimensions of the BRI, viewing it primarily as a geopolitical initiative. Proximity extends beyond geographical distance to include shared history, cultural affinities, and economic interdependencies that profoundly shape how the BRI is perceived and how people view themselves in its light (or shadows).

The spectrum of visibility operates on another, more temporal, axis—local experiences of subtle and gradual changes become normalized within development logics. At the same time, large-scale projects create a spectacle that blinds observers to such subtler shifts. Although a politics of sight considers what is seen and hidden, changes manifest gradually and subtly. In a sense, what might be regarded as violence or dispossession early on becomes normalized or accepted. Over time, changes such as lost land, improved connectivity, increased labor presence, or traffic congestion become part of the landscape, perceived as a natural progression that aligns with development expectations.

Conclusion: A politics of sight from the ground

Grounded, project-based analyses are imperative to avoid oversimplified narratives about China and to illuminate the less visible aspects and effects of infrastructural becoming. Employing a politics of sight holds the promise of development in tension with less visible forms of infrastructural violence. As such, it reconciles the initiative’s ambiguity and spectacle with its grounded manifestations, avoids conflating individual projects and the whole BRI, and emphasizes what La Mela (2024) calls “methodological mutualism.” There is no cohesive way of seeing the BRI, and how actors are seen in its light is contingent. However, more than highlighting diverse perspectives, this approach has the potential to show the social and political consequences of different ways of seeing and what is hidden.

More broadly, this approach addresses a critical challenge of studying Global China: to balance China’s rising presence and power with local dynamics, contingency, and agency (Joniak-Lüthi et al., 2022). All are central to the production and consumption of the BRI. Finally, a politics of sight underscores that the BRI’s power is not solely material. Instead, power is derived from ways of seeing or not seeing the BRI and how it shapes how people are seen. This approach yields insights for understanding global China by questioning prevailing narratives, attending to host country dynamics, and emphasizing the localized experiences and responses to the initiative. As projects are implemented in diverse contexts and encounter friction, it is crucial to examine the BRI’s emergent nature in place, how localities shape projects, and to attend to their diversity of meanings. To grasp the BRI’s rapidly shifting meanings and effects, we must examine not only what is hypervisible but also what is concealed.

This contribution is based on a Book Chapter. Please use the following to cite:

DiCarlo, J. Forthcoming in 2024. Behind the Spectacle of the Belt and Road Initiative: Corridor Perspectives, In/visibility, and a Politics of Sight. In Seeing China’s Belt and Road, edited by Rachel Silvey and Edward Schatz. Oxford University Press.

References

Bentley, Julia. 2022. All Politics is Local: Insights from Malaysia on the Belt and Road Initiative. Transformations: Downstream Effects of the BRI. Available from: https://munkschool.utoronto.ca/belt-road/research/all-politics-local-insights-malaysia-belt-and-road-initiative-0

Davis, Mike. Planet of Slums. New York: Verso, 2006.

DiCarlo, Jessica. 2024. Speed, Suspension, and Stasis: Life in the Shadow of Infrastructure. In Infrastructural Times: Temporality and the Making of Global Urban Worlds, edited by Jean-Paul Addie, Michael Glass, and Jen Nelles. Bristol University Press.

Henry, Jacob. “Morality in Aversion?: Meditations on Slum Tourism and the Politics of Sight.” Hospitality & Society, 10, 2, 2020, pp. 157–172.

Karrar, Hasan H. 2022. Just add infrastructure? Ambivalence towards BRI in unremarkable places. Transformations: Downstream Effects of the BRI. Available from: https://munkschool.utoronto.ca/belt-road/research/just-add-infrastructure-ambivalence-towards-bri-unremarkable-places

Joniak-Lüthi, Agnieszka, Alessandro Rippa, Jessica Clendenning, Jessica DiCarlo, Matthew S. Erie, Max Hirsh, Hasan H. Karrar, et al. 2022. ‘Demystifying the Belt and Road Initiative’. Fribourg, Munich and Boulder. https://bri.roadworkasia.com/.

La Mela, Verena. 2024. Methodological Mutualism: Rethinking the Agency of Local Communities in the Belt and Road Initiative. Transformations: Downstream Effects of the BRI. Available from: https://munkschool.utoronto.ca/belt-road/research/methodological-mutualism-rethinking-agency-local-communities-belt-and-road-initiative.

Larkin, Brian. Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria. Durham: Duke University Press, 2020.

Larkin, Brian. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology, 42, 2013, pp. 327–343.

Oakes, Timothy. 2021. The BRI as an Exercise in Infrastructural Thinking. Transformations: Downstream Effects of the BRI. Available from: https://munkschool.utoronto.ca/belt-road/research/bri-exercise-infrastructural-thinking.

Pachirat, Timothy. Every Twelve Seconds: Industrialized Slaughter and the Politics of Sight. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Star, Susan L. “The Ethnography of Infrastructure.” The American Behavioral Scientist, 43, 3, 1999, pp. 377–391.

Schwenkel, Christina. “Spectacular Infrastructure and its Breakdown in Socialist Vietnam.” American Ethnologist, 42, 3, 2015, pp. 520–534.