Event Report: A New Twist in Female Political Representation in Japan

On March 8th, 2024, Margarita Estevez-Abe, associate professor of political science at Syracuse University, delivered a presentation on female Japanese political representation with a specific focus on Tokyo city assemblies.

Professor Estevez-Abe began by presenting a comparison between female political representation in Japan and other advanced democracies. She pointed out that Japan is frequently ranked among the lowest in gender equality rankings even when compared to other countries with strong male chauvinist cultures like Spain. Three factors were emphasized for Japan’s low rates of female participation in politics: culture, institutions, and political gatekeeping.

Estevez-Abe then delved deeper into the three factors in the context of Japan. Low female political representation can be partially attributed to supply-side cultural factors preventing women from joining politics. Institutionally, there are different electoral systems at the prefectural and national level with few women being elected for proportional representation at the national level. Lastly, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) is a significant political gatekeeper, as it is the dominant national party in Japan but also one of the least progressive on gender issues.

However, despite the low rates of female political participation in Japan at the national level, there has been a rise of women in Tokyo politics. Estevez-Abe displayed a graph showing participation rates of women in city councils, with some cities like Suginami having female representation upwards of fifty percent. She adapted the argument of economist Gary Becker, who described American racial discrimination as a competitive disadvantage for discriminating firms. With increasing numbers of women in universities, the human capital of Japanese women is increasing, however gender inequality in terms of work-family reconciliation is still incredibly high. This paradoxically increases the number of strong female political candidates at the city level, as being a city council member is not financially beneficial for educated men, but the opportunity cost is lower for educated women. Thus, opposition parties to the LDP tend to recruit women, who are more likely to be elected than men, creating a virtuous cycle of female political participation in city assemblies.

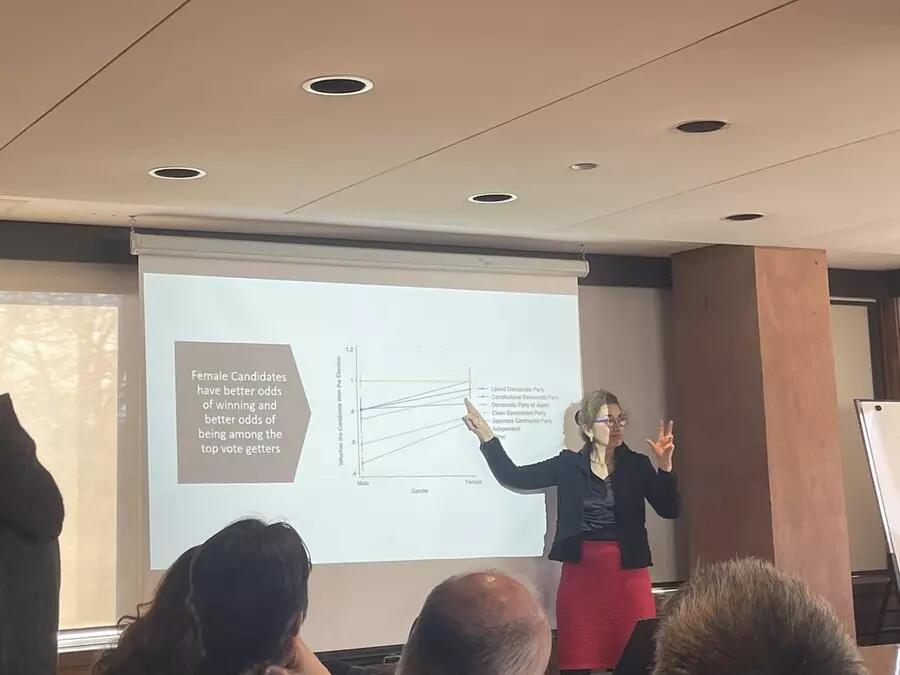

Estevez-Abe presented three hypotheses in terms of Tokyo, suggesting that the female share of participation is inversely related to LDP vote shares at the district level, female candidates are better in terms of electability, and newer political parties that are disadvantaged in recruiting male candidates are recruiting women. She showed various graphs proving female candidates have far better odds of winning elections, particularly for opposition parties, and that professional women tend to do far better in political parties, even in the LDP.

Estevez-Abe then explored the question on why the electability of women at the local level of government is not translating to recruitment of women at the national level. She pointed to three aspects of Japanese national politics, namely institutional barriers at the national level, strong incumbency biases against women, and the lack of a two-party system with the LDP having the majority of government representation while being the least friendly to women.