In 2019, the Trudeau Centre for Peace, Conflict and Justice introduced Indigenous Cultural Competency Workshops to all of its students. This was in recognition of the inherent importance of Indigenous issues, but also because we consider it critical to the education of students of peace, conflict and justice in Canada.

At the Trudeau Centre, we condemn the systemic racism that is a lived reality for Indigenous peoples and people of colour in Canada and other countries. This workshop is a humble step towards listening to Indigenous voices and equipping our students with the knowledge and education to begin the work of eradicating these prejudices.

Earlier this month, our newest cohort of PCJ students had the chance to participate in the workshop, Speaking Our Truths: The Path Towards Reconciliation, again facilitated by John Croutch. They spent the morning identifying key historical events that have impacted Indigenous Peoples, which will inform our students’ practice, working with and for Indigenous peoples; recognizing attitudes and values which further professional self awareness and foster healthy relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people both in the workplace and in the community; and discussing the discomfort Canadians feel when confronted by Indigenous topics.

We are grateful to John and the Office of Indigenous Initiatives for sharing this invaluable opportunity to learn with our students. Miigwetch!

Read on for some reflections and takeaways our students shared following the workshop.

Anya Haldemann

As a Canadian who has spent most of my life outside of Canada, I found the detailing of Indigenous histories invaluable. The workshop, while at times harrowing, was wholly eye-opening and initiated a necessary dialogue of understanding.

Croutch further illuminated these histories with personal anecdotes. His two younger brothers faced challenges reading because of their lack of education from quitting school so early, so they never developed the vocabulary or ability to synthesize what they were reading. His two older brother also suffered from substance abuse as a result of being targets of racism.

In wrapping up his workshop, Croutch ended with a poll: “What percent of Canadians in the following regions think reconciliation is important?” The province with the highest percentage was BC, with 50%. I was left floored and realized why this workshop is needed, specifically for PCJ students: these are the statistics we face in the pursuits of equity and inclusion, and, of course, justice. In understanding this, we know how to better prepare to overcome statistical challenges.

Change is needed, but it should not take these tormenting accounts to persuade Canadians of the need for reconciliation. As PCJ students, we now better understand that challenges of inequity continue to be misconceptions and purposeful exclusion. For this reason and many others, we must stand in solidarity with the Indigenous peoples of Canada in pursuing their justice.

Abhay Sachal

Reconciliation starts with all of us. It is about fostering dialogue, changing perspectives, and creating collective action. Attending the Indigenous Cultural Competency Workshop as a part of PCJ allowed me to reflect on and delve deeper into the colonial history of Canada.

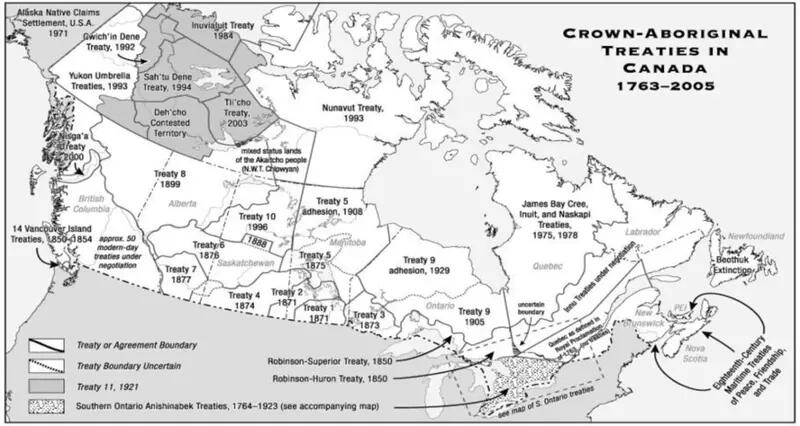

Personally, much of what I know about Indigenous history comes from my high school education. I learned about the legacy of residential schools, the manipulative nature of treaty negotiations, and rampant violence across North America. I was also very fortunate to be able to interact with and work with local Elders as a part of my school district’s Indigenous equity committee. I am also in an introductory Indigenous Studies course (INS201) right now and am pursuing a minor in Indigenous Studies.

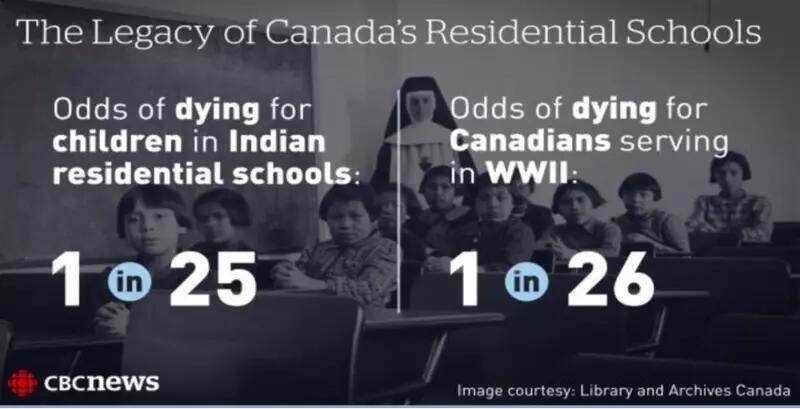

As a student majoring in Global Health and PCJ, I have come to recognize how injustices facing Indigenous peoples today stem from our nation’s colonial past. The presentation by John Croutch drew links between residential schools and intergenerational trauma many survivors face today. I think it is critical that we use the context of our past to find solutions to problems facing Indigenous peoples today. In the true spirit of reconciliation and decolonization, Indigenous sovereignty in decision-making is key.

Ultimately, taking part in this workshop helped me understand my role in reconciliation. As a Canadian, it is my responsibility to learn more about the past and work with Indigenous peoples to create positive change for the future.

Megan Sutherland

Croutch engaged in emotional labour and recounted neglected historical events in order to present my PCJ260Y1 class a message and mandate of reconciliation. Like all PCJ students, as I consider myself to be actively engaged in the pursuit of justice, I must first and foremost be concerned with the injustices which govern the soils on which I study, work and play.

I must recognize Indigenous autonomy in shaping my definition of decolonization, so not to feed into the practice of misusing the term as a tool by which to appease my settler guilt. And it is guilt I felt in listening to Croutch’s presentation, in hearing him recount stories of his mother repressing her mother tongue, and of his brothers being abused for the colour of their skin. However, this is not a form of guilt that I intend to pacify. It is a motivating agent, a sense of urgency which I will focus and apply at the lead of Indigenous voices, scholars, elders and activists. I am not a white saviour nor do I intend to play the role of one. I am a treaty person, and I am grateful to Croutch for having given me guidance on how to begin to act like one.

Lily Yu

I came to Canada three years ago, and one thing that stood out to me at the First Year Orientation was having Land Acknowledgements at the beginning of events and workshops. However, I didn’t know much about Indigenous history in Canada and the role of treaties until recently when I attended the Indigenous Cultural Competency Workshop. This seminar really helped me gain a more comprehensive, holistic understanding of the structural and systemic injustices against Indigenous people and the importance of reconciliation.