Sustain: Genealogies of American Music and Modernism (Includes Live Music)

A two-part symposium on the genealogies of American music and modernism with a live performance by Florence Dore and guitarist Mark Spencer, that was followed by a Q/A session.

Part 1: Soulsville: Post-Fordist City Space and the Sound of “Urban Crisis” With Eric Lott

Eric Lott took up the wacka-wacka rhythm guitar sound that emerged around 1970 and to a significant degree animated the decade’s soul, funk, and disco music, from Isaac Hayes’s “Theme from Shaft” (1971) to Love Unlimited Orchestra’s “Love’s Theme” (1973) to Bobby Womack’s “Across 110th Street” (1973) to “Be Thankful for What You Got” by everyone from William DeVaughn (its writer) to Curtis Mayfield (1972-74) to Carl Douglas’s “Kung Fu Fighting” (1974) to Mandrill and Michael Masser’s “Ali Bombaye” (from the 1977 film The Greatest). Less a song than a sort of sudden sonic infrastructure or DNA strand that came and then went along with the emergent world it announced, the alternately choked and flaring wah-wah guitar, key musical signifier of early- to late-70s inner-city street-level grittiness and keynote of numberless TV cop show soundscapes, organized a vision of a new urban scene that it articulated better than any contemporaneous social scientist. It captured a mood, a demeanor, a disposition, and a perception before and as these latter came to be articulated in the mouths of city denizens, players, and activists. How might it be that a non-representational instrumental figure with a complex musical genealogy, Lott discussed, could come immediately to convey certain social facts and facts of urban feeling in the years of high “urban crisis” rhetoric?

Part 2: “The Daemon Lover,” Bob Dylan, and the New Critics: Vernacular Music and the High Literary

*Note: This presentation included a musical performance with Florence Dore and guitarist Mark Spencer.

In 1916, English musicologist Cecil P. Sharp and his assistant Maude Karpeles traveled to the mountains of Tennessee, Kentucky, and North Carolina to see whether there were ancient English ballads still being sung in the rural U.S. South. There were. In a North Carolina Mountain town called Allanstand, they found a forty-four-year-old woman pregnant with her tenth child, one Mary Sands, who sang for them a seventeenth-century ballad entitled "The Daemon Lover." As Sands sang, they transcribed, and Sharp published "The Daemon Lover" in his 1917 anthology English Folksongs from the Southern Appalachians. Half a century later, Bob Dylan recorded this very same ballad during his second recording session ever, for Columbia Records in New York.

Between Sharp's written transcription of "The Daemon Lover" in North Carolina and Dylan's 1961 taping in Columbia's New York studios, two Vanderbilt professors responsible for hatching the mid-century literary movement called New Criticism wrote novels based on ballads. Robert Penn Warren takes his plot for The Cave (1959) from the 1925 hillbilly ballad "The Death of Floyd Collins," and it was none other than "The Daemon Lover" that Donald Davidson adapted for the novel he wrote in 1953, The Big Ballad Jamboree. (It was postuhumously published in 1996.) "The Daemon Lover" also appears as both printed lyric in Understanding Poetry—the wildly influential New Critical literary tome that Warren edited with Cleanth Brooks in 1934—and as a banjo recording on the Folkways Anthology of American Folk Music. Folklorist Robert Cantwell has described this set of recordings as "the enabling document" of the American folk revival, and rock write Griel Marcus maintains that it was the source for Dylan's enigmatic Basements Tapes, which he recorded with the Band in 1967 withheld from the public for almost a decade.

How shall we understand the fact that the Bard of Rock, as Dylan has been dubbed, shared an interest in the very same ballad as bourgeoning New Critic and brutal segregationist Donald Davidson? How is it possible that "The Daemon Lover" both stands as defining literature itself in Brooks and Warren's volume and gives rise to the American folk revival? In this talk, Professor Florence Dore (UNC Chapel Hill) showed how tracking the life of "The Daemon Lover" clarifies a profound connection between cultural forms that have been understood in opposition to each other. What we have considered to be high literature, reserved for study within university bounds, turns out to be utterly enmeshed with vernacular music, a popular form widely available to all. This is no minor claim. Indeed, unpacking the role of vernacular music in American conceptions of high culture helps us better understand the crucial problem of civic belonging, an issue that defines the current political landscape in the United States. The widespread sense of disenfranchisement in the present has led to a damaging skepticism about democracy as a legitimate form of government. The history of vernacular music contains within it the seeds of inquiry into what counts as "the public" in democratic life, and thus serves as defining in what is now known as "the public humanities."

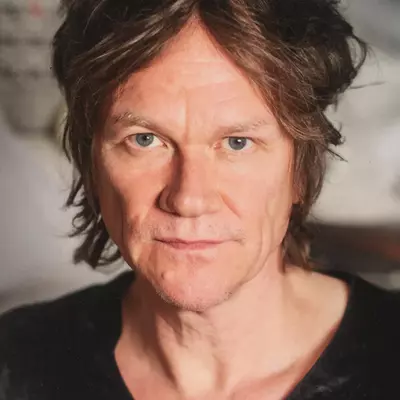

This talk was part of a traveling public humanities program that aims to address the crisis in what defines a "public" by bringing discussions about these topics into public settings. The Ink in the Grooves Live, or Ink Live, consists of events that combine discussion with one of the most engaging and accessible cultural forms: live music. Professor Dore was joined by the eminent guitarist Mark Spencer. Mr. Spencer has accompanied a wide range of artists, including Chrissy Hynde of the Pretenders and Laura Cantrell. He is a current member of the influential Americana band Son Volt.