A Political Pandemic: Partisanship and Chaos in the American COVID-19 Response

The United States government’s response to COVID-19 is a story of decapitated federalism. Press conferences, rife with gaffes and misinformation, have broadcast the White House’s flagrant abdication of public leadership. As state governments in outbreak hotspots flail under depleted budgets, insufficient testing capacities, and personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages, the White House and its federal agencies have failed to coordinate a national response to the pandemic. The primary policy used to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 has been social distancing, enforced by state governments through executive orders limiting gatherings and various business sectors. These orders, in both their timing and stringency, have been defined by a nearly unanimous partisan logic.

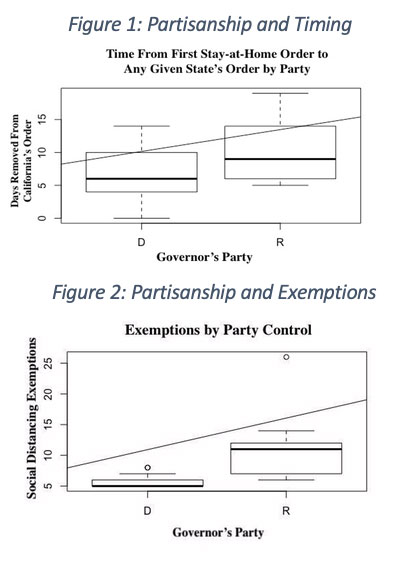

Republican governors implemented social distancing later than Democratic governors. Republicans also included significantly more exemptions in their social distancing orders. Fourteen states attempted to reopen their economies less than a month after social distancing orders were first implemented by introducing sector-wide exemptions. Thirteen of these have Republican governors. Given data on a state’s number of exemptions and its delay in ordering social distancing, one can use statistics to predict the governor’s party correctly ninety-nine percent of the time. Unlike many countries with major outbreaks, the US has not implemented a nationwide lockdown at any point since its first case was detected in January.

The discordant nature of state social distancing orders is just one example of the country’s disjointed federal response. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) commands an emergency medical stockpile built to respond to infectious disease outbreaks by efficiently distributing supplies to regional hotspots. However, FEMA and the White House have refused to release information on where these supplies are going and how allocation decisions are being made. The administration has also failed to organize a single point of purchase for new equipment, leaving the market open for medical suppliers to gleefully watch prices skyrocket as states struggle to source scarcely available gear. While the European Union financed procurement schemes across countries to increase their buying power for medical supplies, the United States’ federal government was bidding against its own states, who were in turn bidding against each other.

The federal government has taken significant action on one issue: the cataclysmic economic fallout of COVID-19’s shock to consumer spending. The CARES Act was signed into law on 27 March 2020. Its main focus was the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), a low-interest loan program for small businesses to fulfill payroll obligations as revenues plummeted. The legislation also includes increases in Unemployment Insurance (UI) payments, to the tune of USD 600 a week, and a one-time $1,200 cheque to all non-dependent taxpayers making less than $99,000 a year. Although this financial stimulus is historically generous, it has not sufficiently mitigated the economic destruction wrought by COVID-19.

Many small businesses, especially restaurants, have much higher rent than payroll, limiting the potential relief a PPP loan can offer. Meanwhile, the White House has resisted disclosing the names of businesses receiving PPP loans to the General Accounting Office, giving credence to fears of executive obstruction in ongoing and future stimulus oversight efforts. Increased UI benefits last only through July and will expire without new legislation. But unemployment remains at its highest levels since the Great Depression, and food insecurity has already risen in low-income households: 40 percent of children under the age of twelve who live with single mothers do not have enough to eat.

Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic Americans have been affected more severely by the coronavirus pandemic than White Americans. As a result of more common comorbidities stemming from social disparities, including higher rates of heart disease and diabetes, many racialized communities have seen more fatalities than White communities. Take Michigan, for example: Black Americans represent 12 percent of the state’s population and more than 40 percent of its fatalities from COVID-19. The Navajo Nation is currently experiencing the highest per capita infection rate in the country. In California, Hispanic people make up 39 percent of the state’s population, and 56 percent of its COVID-19 cases.

The murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and other Black Americans in recent weeks have spurred a wave of protests condemning decades of police violence against Black communities. As protestors are crammed into city streets and public plazas, gassed by police with a respiratory irritant that causes uncontrollable coughing, and bussed to overcrowded city jails, it is plausible the US could see a resurgence of COVID-19 in dormant hotspots like New York and Detroit. Widespread social unrest, catastrophic economic fallout, and new outbreaks emerging across the country will pose significant challenges to the federal government and states in the coming months. These challenges come in the midst of the United States’ most politically charged presidential election since 1968. Whatever the outcome may be, the next five months will be a defining period in American history.